About La LaBoriVogue

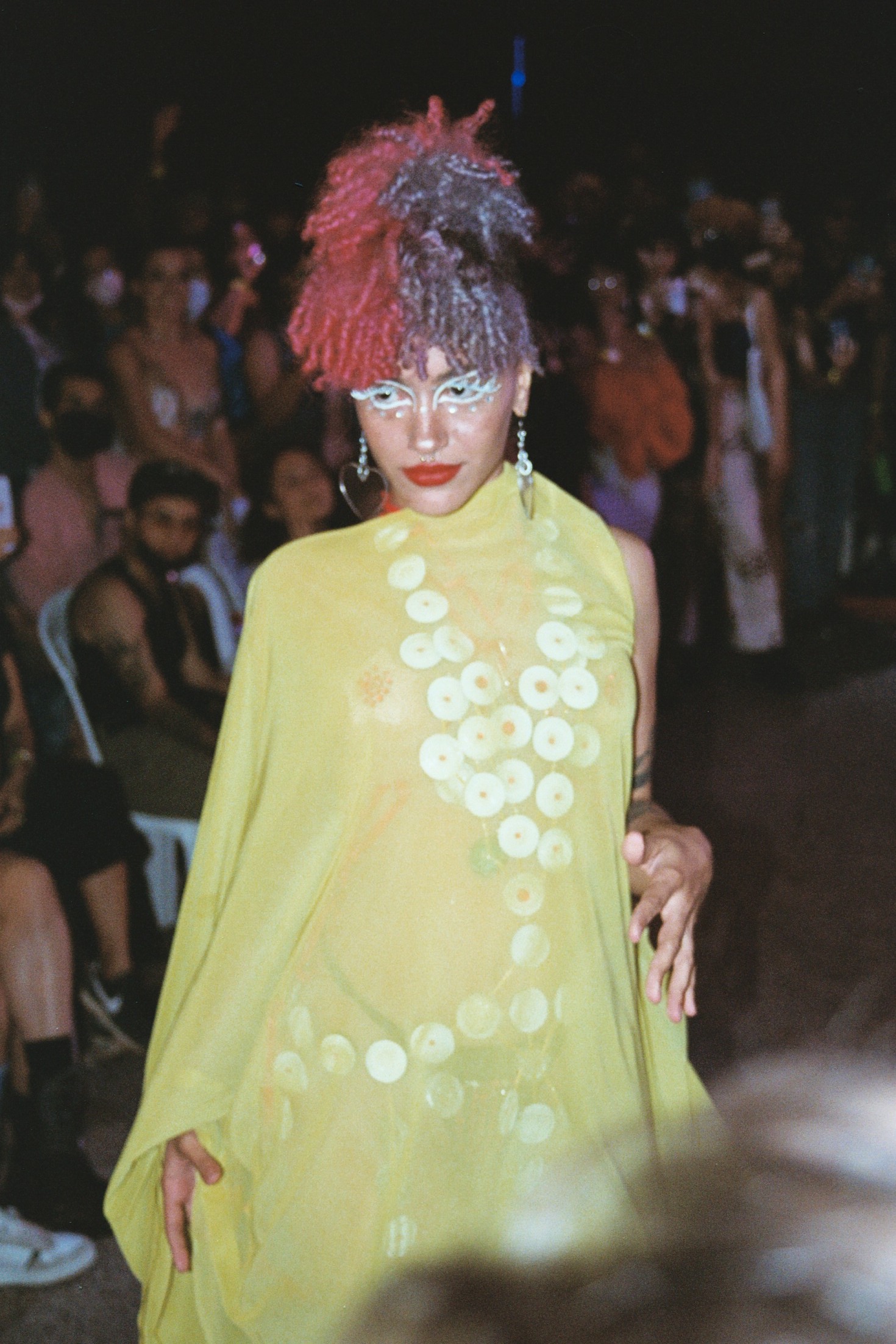

Excerpts from the conversation between Edrimael Delgado Reyes, father of LaBoriVogue, and Fortuna. We talked about its creation, the need for spaces like that, the history of the ballroom scene, the centrality that Puerto Rico has had in its creation and the links of LaBori with the art world. March 2023, San Juan and Lausanne. Photos by Ana Paula Teixeira

Everything began in the middle of the pandemic when we were locked up. On July 15, we gathered a group of friends and started to meet every Wednesday or Saturday. It was once a week. I bought a speaker that still exists—it’s the survivor; it cost about 80 dollars. That speaker has been exposed to the sun, salt, sand, and everything, and it’s still alive. We started to do practices with that speaker. It was a moment to share our ballroom knowledge. It’s called LaBoriVogue because it’s an acronym for “Laboratoria Boricua de Vogue.” People think “La” is an article from “Borivogue.” It’s not. It’s “La” for “Laboratoria.” Laboratoria comes from the notion that I don’t have all the knowledge. It is a space for experimentation and sharing knowledge around a practice or discipline – in this case, a ballroom. People responded to that open call because I had done ballroom activities since 2018.

I had started voguing classes at events at El Local, which was the first place where we were allowed to do an event in Puerto Rico. In fact, it was El Local that invited us to do an event in their space. This very punk and alternative space in Puerto Rico influenced independent artists’ development throughout the 2000s. I had already done three events when we started there in 2018-2019. By 2020 I submitted a proposal to the Open Society Foundation. They approved it, and that’s when we started meeting under LaBoriVogue. Before that, it had been my independent practice as an artist. That was the first grant we earned. Then we got a grant from the Puerto Rico Arts Initiative (PRAI) and Centro de Economía Creativa. We are basically surviving from grant to grant and from fundraiser to fundraiser. Now we have started to become a non-profit association. It’s another serious formalizing step. That was something I hadn’t thought I would do because it was a collective for me, but since we are handling large amounts of money, it’s a step to take.

It has grown over time. In the beginning, it was me. People referred to me as LaBoriVogue. What people consider to be LaBoriVogue has been changing. Before LaBoriVogue was a collective project, it wasn’t considered a house. When the first five members, Mussa Medussa, Shadiel Orlando, Mecha Corta, Roberta Acosta and myself, went to Mexico City to share with the ballroom community, we started to perceive ourselves as a house. I had always avoided that notion because of many personal things. But that’s another conversation. I didn’t want to be a house because LaBori was more of a cultural platform that could generate ballroom culture in Puerto Rico, and that could be a space to generate houses. That’s eventually what happens. Also, LaBoriVogue itself becomes a house. That’s when more people came to the project. We realized that, beyond the people we were working with, many people began to want to collaborate with and be part of LaBoriVogue. Suddenly many people joined us, the crew started to grow and expand, and there were fifteen of us.

Our main objective is to educate about ballroom culture. The other most important thing is to generate ballroom culture by doing the events. One thing can’t exist without the other. I can’t throw a ball when people don’t know how to walk categories. Our educational program consists of public practices in Plaza Barceló at 8 p.m. We go there, everything is free, whether people know about it or not, you can smoke a phillie, you can attend, there is no structure, there is no teacher, it starts at the time you want, you warm up however you want, you do whatever you want. It is a meeting in a square. We also do a cycle of workshops in La Goyco every Friday at 6 p.m. Those spaces allow you to learn about categories, and public practice is the place to practice them. That way, people aren’t newbies when they walk their category when the ball comes around. The practice spaces and the educational spaces around ballroom culture are equally important and work to nourish ballroom events.

Ballroom in Latin America is not different structurally. It is the same ballroom. There are the same categories, and they are walked in the same way. Still, the issues and needs of their communities are different from the issues and needs of those in the United States. Although now the United States is at a very retrograde stage in its history, it’s ahead in terms of human rights and LGBT activism. New York is where all LGBT activism begins, or at least that’s what we’ve been led to believe. There has been activism in other places, but for it to be part of official history—that’s another story. There exists a privilege that has to do with the Empire, and that has to do with economic resources and access, with the activist policies that exist in the United States that do not exist in Latin America. Something as simple as same-sex marriage or transgender people’s access to care. Simple things like that, which in the United States, or at least in New York, may seem so normal, in the rest of Latin America, they are not so simple, and even less so in the Caribbean.

So Puerto Rico is in between. It is in a privileged position compared to the rest of Latin America, but also in a state of precariousness, in a strange liminal zone in relation to the rest of America. All of that makes the scenes in Latin America different, especially in Puerto Rico, where there is the question of the colony. That is another layer of information that has to do with liberation. That’s why from the beginning, I’ve been formulating the project as a project of liberation. Not only because I think that the project can liberate the body and mind and free us from the bonds of patriarchy reflected in the body. The bonds of patriarchy have to do with political bonds because patriarchy is what fosters the colony, patriarchy is what fosters violence, and that violence is colonial. The colony has to do with non-independence, and non-independence has to do with the non-independence of the body. The macro and the conceptual are reflected in the micro. Sometimes people feel that LaBoriVogue is not a political project because we are not making public policy. Still, my public policy is to change ourselves, to understand who we really are inside and to be able to live from that wholeness. This is completely anti-patriarchal and anti-colonial. The project has that political connotation. It’s not like I’m always standing there with the Puerto Rican flag saying, “Free Puerto Rico.” Our actions show we are moving towards liberation in all aspects of life.

People have received the balls very well since I started throwing them. People need that kind of space. The only thing that existed here was drag. I feel that the ballroom opened other doors, drag didn’t have to be the only one. Ballroom can be another manifestation. The fact that you can show your talent and earn money opens another door to possibilities. It connects you. It creates a nucleus within the economy that is called social capital. The capital generated is not necessarily in a financial exchange but in a social exchange that enriches the economy but does not depend on it. It is a network of exchange. People would be lying at home with their talent and unable to use it if the platform didn’t exist. It is a space that they needed, that has given them another life.

Earlier, you asked me the difference between ballroom in Puerto Rico and New York, right? Well, it’s in the categories, the taste, the passion, and the categories’ approach. The sex siren is not walked the same way. The perceptions of gender in the categories also differ because our gender struggles are different. Being non-binary has more space here than in the United States. These are conversations that they haven’t had. Now they have started to open categories that are gender non-conforming performance or gender non-conforming face, but it didn’t exist before. The first ones to introduce these categories were Latin America, Chile, Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, and Puerto Rico. Our vision of gender is a decolonial vision that has to do with our history. It is not necessarily the version of gender that the United States has, which is very binary. If you are going to transition there, más vale que sea en una mujer. That thing of the in-between, of the non-binary, now I feel that it is becoming visible within the ballroom.

Ballroom is boricua - gagagagagaga! Hahaha. I feel that this is one of my forever arguments. I have texts and essays about the relationship between Puerto Rico and the United States and the great influence of migration from Puerto Rico in New York that changed not only ballroom but culture at a macro level. The development of salsa, the development of latin jazz, the development of slam poetry, hip hop, and rap. In all those movements that were Afro-American, that were black, there were Afro-Puerto Ricans. It is summarized as Latinos because we are labeled as Latinos in the United States. Yes, there were many Caribbean people. There were many Puerto Ricans, Dominicans, Jamaicans, and Cubans. House music could not have developed if it were not for the rhythmic influence of the Caribbean islands. It is real. If they try to hide it, that’s a lie. The influences of rhythm and movement influenced how voguing is danced because there’s movement in the shoulders. Crystal LaBeija, the person who is credited with the creation of modern ballroom, decided to create her own scene where black trans people are privileged and where another type of beauty other than white beauty is privileged precisely because she did not win in drag competitions she competed in the 70s. She was called Crystal LaBeija because all her boricua friends called her “la bella.” “House of LaBeija” is a mispronunciation of “la bella.” Even in those stupid details, you can see the influence of Puerto Rico on the ballroom scene. DJ Vjuan Allure, one of the great DJs that changed ballroom music and made it sound the way it is, was born in Ponce in 1965. The invention of the crash, the HA! you hear in the music, Vjuan Allure was one of the people who established it. Vjuan Allure was Puerto Rican. Currently, Luna Khan is the planner of the Latex Ball, one of the most famous balls in the United States. He is Puerto Rican. House of Xtravaganza, founded in 1983, all the members of House of Xtravaganza were Puerto Rican. There are so many Puerto Rican people in ballroom history. When they say “Afro-American” and “Latino,” well, “Latino” is where we all fit. Come que, no, somos puertorriqueñxs, especialmente afropuertorriqueñxs. Afro-Puerto Rican people fit into black discourse because we are black. After all, it’s black culture. Bringing ballroom to Puerto Rico, not appropriating it but bringing it back, is to recognize that Puerto Rico is black. I feel like there has also been a whitewashing of Latinidad or Puerto Ricanness, and it’s like, no baby, Puerto Rico is a country with African roots. Our culture, rhythms, way of speaking, and being come from there. So, ballroom is also black culture, and we Puerto Ricans have been there since the beginning.

The relationship we have with the art world is strange. We threw a ball at the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Puerto Rico (MAC) at the invitation of Regner Ramos, an architect who did an exhibition called Cüirtopia [2022]. We were invited to the MAC to do the ball. They paid us very little, in fact. We have had no conflicts per se but we did have ideological frictions with the institutions that have invited us because of our way of proceeding. I do not want to say it is anarchic, but it is a very different methodology. We make art for the community and art from the community, with other precepts, with other priorities, and with other needs. It’s not that they can’t fit together, but the ways of proceeding when managing an event are very different. Until now, the MAC has been the only museum that has had us. I feel that LaBoriVogue’s effort is highly valued in the Academy. I have been interviewed every month. I’m about to start charging because there have been too many. The Academy loves LaBorivogue. The Academy loves everything Queer. Sometimes I feel that it’s like profiteering, an absorption of what is Queer to enrich themselves or to study us but not necessarily to benefit us. I feel that in the art world, we’re in it and we’re not. Most of the grants we’ve won have been for activism. Not necessarily art. The one we have now is for art, and it’s a challenge because we are a community project and treated as an art project. I am not using the funds to buy sculpture material, baby, Estoy pagando recursos humanos. Necesito que la gente bregue con sus cosas. So, it’s a strange space because I come from las Artes plásticas. I have an art degree and studied at the San Juan Ballet. I come from the art world, and people know my work from that space. But the rest of the crew does not come from that same place. It is a project that inhabits and moves within both worlds. I do feel that it has influenced culture a lot, inside and outside the art world. It has changed how Queer people move within the city. That is a very cultural aspect of LaBoriVogue. Thanks to LaBori, other Queer activist spaces have emerged. LaBori, in turn, is part of a Queer history that precedes me and that precedes LaBoriVogue. I feel it is more tied to the history of activism and performance than art. We occupy an uncomfortable, hybrid space. We put up a banner at the MAC that caused them problems: “Utopia is a country without gringos.” The MAC had to write a press release to defend the banner because the Partido Nuevo Progresista (PNP) started criticizing the museum and saying, “Why are you using public funds to criticize gringos?” I feel that LaBoriVogue puts real issues on the table that are pertinent and that need to be talked about.

Taken from issue 2 – Buy here