Ana Navas

The washing cycle, an interview with Ana Navas

How long have you been living in Rotterdam?

Hoping around from residency to residency and living as a nomad became more difficult as the pandemic started. The Netherlands was always a place that I came to back and forth to since my residency in De Ateliers [Amsterdam] and where I already had a lot of friends. I like it here; it’s a good option for a stable home until the madness subsides—if that ever happens. But in reality I’ve been in Rotterdam for very little time. [I’ve been] more properly installed since October when I returned from Mexico City after the exhibition at Pequod Co.

Before that where did you have your studio?

I was in a residency called Fiminco, a program in Romainville, in the outskirts of Paris. I was there for ten months. The facilities there were quite good and that’s where I practically did all the production of the Pequod Co. exhibition.

How has moving around influenced your practice?

There is something quite hard to specify in the residencies’ applications when they ask for a certain project to be done in a place where you might never have been to. The initial idea might differ from what you end up doing. So, in that sense, I feel sometimes the place where I am determines a lot about the production. On some other occasions it doesn’t. What seems to me more organic and sincere is to propose an investigation that is ongoing. In regard to the hands-on production moment, one of the main reasons I work with textile is because it is easy to transport. It’s interesting because textile has a whole backstory in trading commerce. Other materials that I end up using are much more related to what I find on my way.

For example, the plate series started in a residency called Charco Granero in Leon, Guanajuato. It was very interesting for me to arrive there and see the quantity of plastic and vinyl available from the shoe-making industry going on in that town. Even though I had researched it previously on the Internet, nothing compares to being in the actual place. So there are some things that I adapt to as I go, things that are quite hard to foresee. What I do plan beforehand is how I’m going to take everything with me afterwards.

Do you usually take some base materials with you where you go?

There are some bits of fabric I take along with me—I don’t know where or in what works they will end up. Sometimes they can travel with me for months and not be used until I find a suitable moment for them.

You have some ongoing series of work, such as the Presidents series, which you plan to carry out during your lifetime. What interests you in such long-running projects?

I’ve always liked in museums when you see an examination of a certain subject, sequenced by decades. The Presidents series consists of writing the names of the current heads of state in the world on rice grains and placing them on a child’s garment that reflects the specific trends of that time—and which I then take as a base for those grains. It aims to be an abstract, material historic document. I’m not interested in doing things that are literally political in my work; it’s more pleasurable for me to focus on the material qualities, or the recognition and associations a viewer can have when encountering the objects.

Tell me more about how you understand these material historic documents and how the idea of archive translates into your work.

I think it’s interesting to have a framework that reveals where some of the references in my work come from, those being monuments, history of fashion, modern sculptural language, etc. It’s a bit like when an artist presents an archive, but instead of photographs or notes, I do miniature paintings on plates. They act kind of as a footnote in the exhibition, which presents recognizable sceneries that have to do with the topics in the exhibition: a research archive translated into a material outlet.

Do you usually adapt ongoing series to the specific topics of an exhibition?

Having the plate series in the Pequod exhibition was like a peek into the idea of display and exhibiting—and how we organize the world, not only in a museum’s context, but also how common objects are arranged in department stores and souvenir shops. Likewise, the transparent textiles in that exhibition had scenes printed on them with empty cabinets; I was not interested in examining the ethnographic artifacts showcased in a museum display as much as in the structures that support them. I also want for these transparencies to be understood in a much more geometrical, abstract manner when seen from a distance.

Tienda de souvenirs, 2021. From the exhibition Aura significa soplo at Pequod Co, Mexico City, 2021. Images by Sergio López, courtesy of the artist and Pequod Co

Todo D’Vidrio, 2021. From the exhibition Aura significa soplo at Pequod Co, Mexico City, 2021. Images by Sergio López, courtesy of the artist and Pequod Co.

Caféothèque, 2021. From the exhibition Aura significa soplo at Pequod Co, Mexico City, 2021. Images by Sergio López, courtesy of the artist and Pequod Co.

Yet far more often than these text based pieces, one would play pure melodies with the mouth organ 3, 2014. From the exhibition I don’t care if this has been standing here for centuries, its ruining my Zen Garden at De ateliers, Amsterdam, 2014. Images by Rob Bohle.

Yet far more often than these text based pieces, one would play pure melodies with the mouth organ 2, 2014.From the exhibition I don’t care if this has been standing here for centuries, its ruining my Zen Garden at De ateliers, Amsterdam, 2014. Images by Rob Bohle.

Yet far more often than these text based pieces, one would play pure melodies with the mouth organ 1, 2014. From the exhibition I don’t care if this has been standing here for centuries, its ruining my Zen Garden at De ateliers, Amsterdam, 2014. Images by Rob Bohle.

I recall an exhibition you did at Ladron in Mexico City in 2018, which took the concept of “power dressing” to create a series of abstract collages. Do you usually think first of an idea or is it an object that leads you to a certain investigation?

I think many things happen at the same time. In that case, I was reading about the topic but at the same time thinking what other fictional objects could relate to the concept of power dressing. It’s very based in the process of combining objects, finding their right placement in a work, and rethinking and rearranging them some days later. I think it’s a bit the same as what happens to you curators: when you think of something, ideas and objects come and find you, not in an esoteric way, but [rather] you start paying more attention to them.

Which qualities in objects make you initially drawn to them?

Their capacity to provoke in me a series of associations. Things that I didn’t see in my childhood but that started homogeneously appearing in my life. Silly examples such as plastic trolleys for luggage or drying racks used in Europe—which, when I first encountered them, I wasn’t sure how to properly use, but that always seemed to me to have a very sculptural aspect. I exalt those characteristics in objects such as vacuum cleaners or baby chairs by creating a costume for them, and I like to see what happens when the object and its performativity is no longer present, when we are just left with this flat covering. Another aspect is that I reflect on their design and where their aesthetic comes from, such as with those [things] which are deemed “minimal” or “futuristic,” thinking about how those concepts are understood when you type them into Instagram for example. And what relations do these things have with the original forms or discourse of that artistic movement? A series of sculptures that dealt with this construction of archetypes was the one made for the exhibition I don’t care it this has been here for centuries, is ruining my zen garden, where I researched how the mental image of the word “sculpture” was depicted in learning books, art supplies or publicity [materials]. My work is about the meeting points between high and low culture and how they influence our notions of taste and the common language, and thinking of an object’s circulation and its extended family of historic or fictional associations. But even if the references are important, I hope the spectator doesn’t need to know them to have an encounter with the object. Sometimes the forms I create clash with their original influence. What I do is a bit like doing a washing cycle, where, after many washes, things return washed out to the starting point.

Pyramide, 2018. From the exhibition Rarely true at Kunstruimte van de Nederlandsche Bank, Amsterdam, 2019. Images by Otto Polman.

Iron, 2018. From the exhibition Rarely true at Kunstruimte van de Nederlandsche Bank, Amsterdam, 2019. Images by Otto Polman.

Your work combines multiple disciplines such as painting, sculpture, sewing and creating installations. Do you do all these processes?

Not all of them. Much of the painting I do myself, but sometimes some friends assist me. For works on fabric such as the costumes for objects, I can have a sketch but don’t know how to technically to execute it, and what I’ll do is go to a fashion designer and dialogue about the different possible ways to do it. I wish I knew more about some processes, but I also think there can be a fortunate distance. For example, I’ve always liked magazines of clothing patterns. I don’t see a piece of clothing there, but I do see these weird shapes that fascinate me—how they appear without a mannequin underneath. I like the idea of being able to appropriate something by not having the original, but through the copy. I’ve had the chance to collaborate with people with other expertises who help me in these processes, but I also like the manual quality and the clumsiness that goes along with the materials I don’t usually handle.

Thinking about some other past exhibitions, you tend to create all-encompassing installations. Is your work usually affected by the space they’re in?

It depends on every occasion and invitation. In the exhibition I had to think of you [Stadtgalerie Sindelfingen, 2017], I had six different spaces to myself; logically, I had to react in a different manner than in a smaller space, thinking about the whole choreography of the exhibition as chapters of certain themes. For To cut one’s hair by the moon [Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden, 2018], the space was small. Luckily I had already seen that space, and I had noticed that if you put few objects in there it looked even smaller, but when adding more, it kind of expanded. I do consider the space, even in a case where most of the works are done beforehand. I might think of creating a gesture that connects everything together or acts as a footnote.

Can you tell me more about the exhibition To cut one’s hair by the moon, which was a body of work created during a specific time frame?

Those were works I made between two haircuts and were about showing the connections between them as a collage. But what really set the timeframe of the exhibition were some leather numbers that read “2059.” That is, supposedly, the final year of my life expectancy. There’s also how that figure could affect my works or not, a year wherein there's sense of whether your market prices will rise or not. I wanted for the spectator to have this overwhelming experience when entering the room and to have the possibility of zooming in to certain works.

Elegance (Sarah-Jane), 2014. From the exhibition I don’t care if this has been standing here for centuries, its ruining my Zen Garden at De ateliers, Amsterdam, 2014. Images by Rob Bohle.

Nespresso, 2014. From the exhibition I don’t care if this has been standing here for centuries, its ruining my Zen Garden at De ateliers, Amsterdam, 2014.

Are there some other works that incorporate your personal history or timeline?

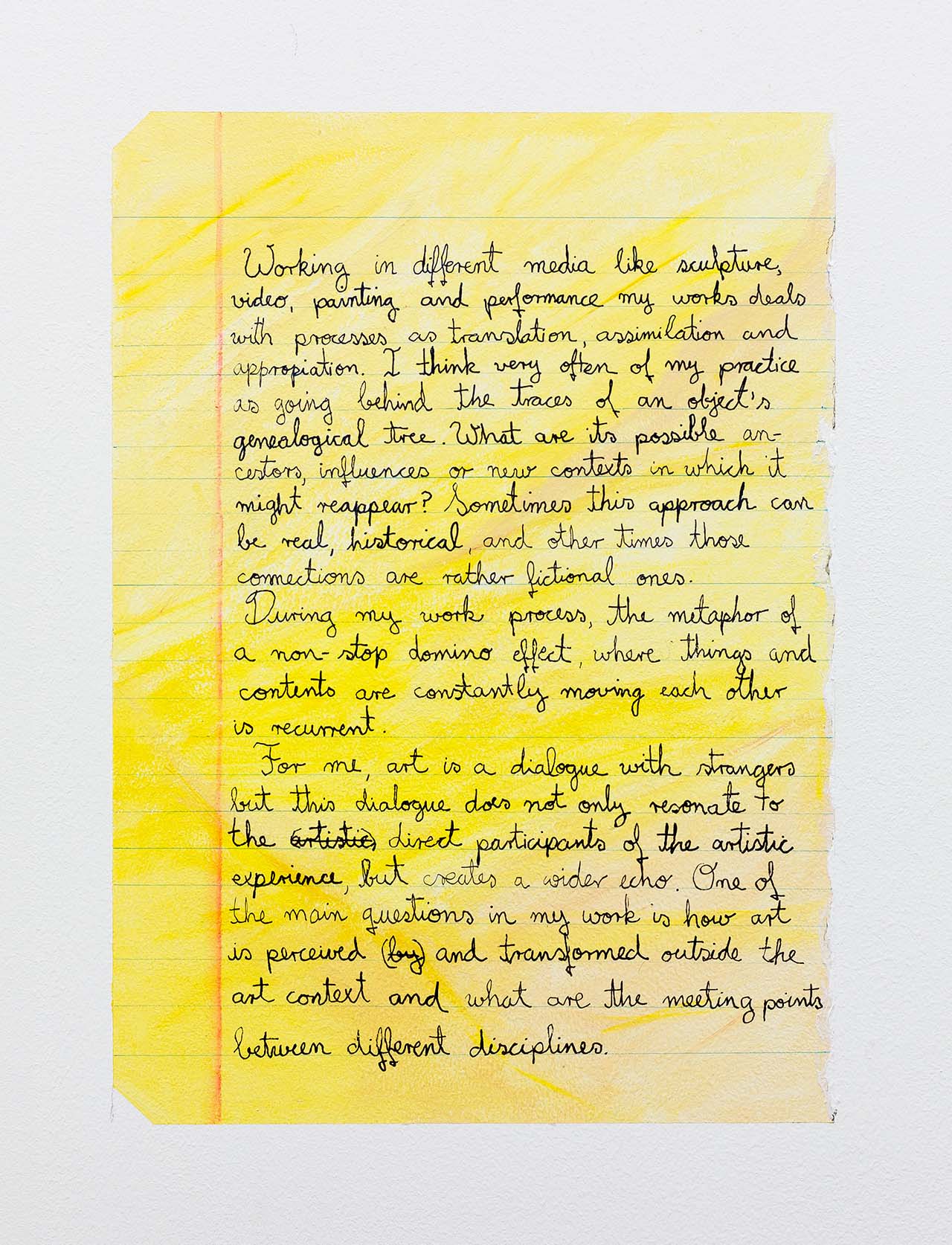

In another exhibition I did with Evelyn Taocheng Wang and Mila Lanfermeijer at Nest in The Hague, there was this letter where I copied a notebook sheet directly on the wall and where I wrote my artist statement, but I did it trying to emulate the calligraphy I had when I was sixteen years old. This is a series that exists in different ages. So, for me, it was quite like doing these time travels to the future and the past through my calligraphy, revisiting how I understood things at a certain age, in a period of trying to find one’s individuality, and dealing with the difficulty of writing something that feels as rigid as an artist’s statement—which is not something to be done in an afternoon. Even the word “statement” feels like a requirement to explain your work in less than two minutes. I’m very interested in the contents of that letter, but also in the materiality of how it was done, how calligraphy is supposedly a very unique and individual expression of each person, even though we use the same alphabet… How, at the same time, it could be written by anybody, as it is in a standard, rounded “teenager's” typography.

What else are you doing right now?

For me, right now is that moment when you just finish an exhibition and the adrenaline rush fades. Even if you are in the studio the whole day, it’s not the same concentration level as when you’re preparing a project. It’s not the same when you are thinking about what you want to continue doing, executing things materially, or when collaborating with more people or in a final process with a curator. I’m reflecting more about past processes that I want to keep doing, but I do think the idea of the mood board will take a protagonist’s place—objects that refer to a future object and that have a bunch of ideas surrounding them, without being the object per se. Thinking about references and copies not for its 1:1 likeness, but for the transformation that takes place in that process.

Ana Navas is a Venezuelan-Ecuadorian artist. From 2004 to 2010 she studied at the Staatliche Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Karlsruhe, where she continued as a Meisterschülerin (MA) with Franz Ackermann. Between 2012 and 2014 she was a participant at De Ateliers Amsterdam, followed by other residencies in France, Mexico, Brazil & Colombia, and has been the recipient of prizes such as the NN Art-Award (2020) & the Kalinowski-Preis Kunstfonds Germany (2018). She is currently represented by the galleries tegenboschvanvreden, Amsterdam; Sperling, Munich; ABRA, Caracas; Crisis, Lima and Pequod Co., Mexico City.

Fabiola Talavera is a Mexican independent curator, writer, cultural manager and archivist based in Mexico City. She has worked with different public and private cultural institutions in Mexico, Australia and New Zealand, in exhibitions, festivals, research projects and documentary archives. She has a degree in Arts Studies and History from the Universidad del Claustro de Sor Juana. During 2021 she worked as head of liaison and international relations at the International Film Festival of the Isthmus. She is currently responsible for the Poesía en Voz Alta Digital Archive and manager of international events at Casa del Lago UNAM. She is a regular writer of essays, interviews and art reviews for Onda MX and Purple magazine.

All images courtesy of the artist.

Taken from issue 1 – buy here